Since the passage of the Energy Tax Act in 1978, tax credits have helped finance clean energy projects. Traditionally, developers that invested in renewable energy technologies have been eligible for either the investment tax credit (ITC) or the production tax credit (PTC). To monetize those tax credits, developers turned to tax equity partnerships, primarily with large banks.

Since the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, the availability of tax credits to finance a larger number of clean energy technologies, including manufacturing projects and critical mineral extraction and processing, has expanded significantly. The legislation made the tax credits transferable, enabling clean energy developers and manufacturers to monetize their tax credits by selling them to a third party. Transferability is catalyzing private investment — Crux estimates that every $1 of federal tax incentives drives $5 of private investment.

This guide examines the differences between transferability and traditional tax equity, including the rise of hybrid tax equity structures that utilize elements from both financing structures.

The ability to monetize clean energy credits has been around since the Energy Tax Act created the ITC in 1978. How the credits can be monetized has changed dramatically, especially since the advent of transferability.

The ITC and PTC are the tools investors, developers, and manufacturers can use to finance projects. Understanding the features of each tax credit and how they differ can help stakeholders determine which is best for their project and the optimal investment structure to pursue:

ITCs and PTCs are the building blocks of clean energy financing deals. How they are used varies depending on the type of project and the parties involved. In traditional tax equity structures, equity investments are structured as partnerships and the investment is made just prior to a project being placed in service. More specifically, about 20% of a tax equity investment is made when the project reaches the mechanical completion stage, while 80% of the capital is provided at substantial completion.

The investment made in a tax equity partnership (also called a partnership flip, or P-flip) helps substantiate a step-up in a project’s ITC basis to fair market value. In exchange for that investment, the tax equity investor receives 99% of the tax benefits along with a small portion of the project’s cash flow and the depreciation attributable to the project. The allocation of tax benefits usually drops (or “flips”) to 5% after the tax equity investor receives an agreed-upon after-tax return. At that point, the sponsor can purchase the tax equity investor’s interest in the partnership after the flip.

Tax equity has historically driven significant investment in clean energy. The complexity and expense associated with tax equity, however, limit the universe of investors to between 10 and 20 large financial services companies with sufficiently sophisticated operations to navigate clean energy credit monetization and depreciation. Similarly, tax equity financing has traditionally been limited to developers with large project portfolios generating large volumes of tax credits.

Tax credit transferability has enabled the direct sale of clean energy credits from project owners to buyers seeking to reduce their tax liability. Buyers pay cash for these credits after they are generated. In the case of ITCs, this occurs when the project is placed in service. For PTCs, this happens when a project begins producing electricity or when a manufacturer produces an eligible product.

The streamlined transaction processes in transferability have enabled small and mid-sized developers to monetize clean energy credits and have widened the pool of eligible tax credit buyers.

In direct transfers, the project’s owner is the seller. The project development company is often a pass-through entity, so buyers usually seek indemnities and assurances from the parent company to ensure the tax credits are eligible to be sold. In this structure, no investment is required in the project. However, the project developer may secure a forward tax credit purchase commitment with a tax credit buyer, which can be used to obtain a bridge loan at relatively lower cost of capital compared to equity financing.

There are several notable differences in tax equity and tax credit transferability transactions. Because tax equity partnerships are complex, their transaction costs often run into the millions of dollars — primarily due to legal fees.

Transferability does not require the same transaction costs as tax equity deals, though some additional costs are incurred to obtain insurance and to complete due diligence.

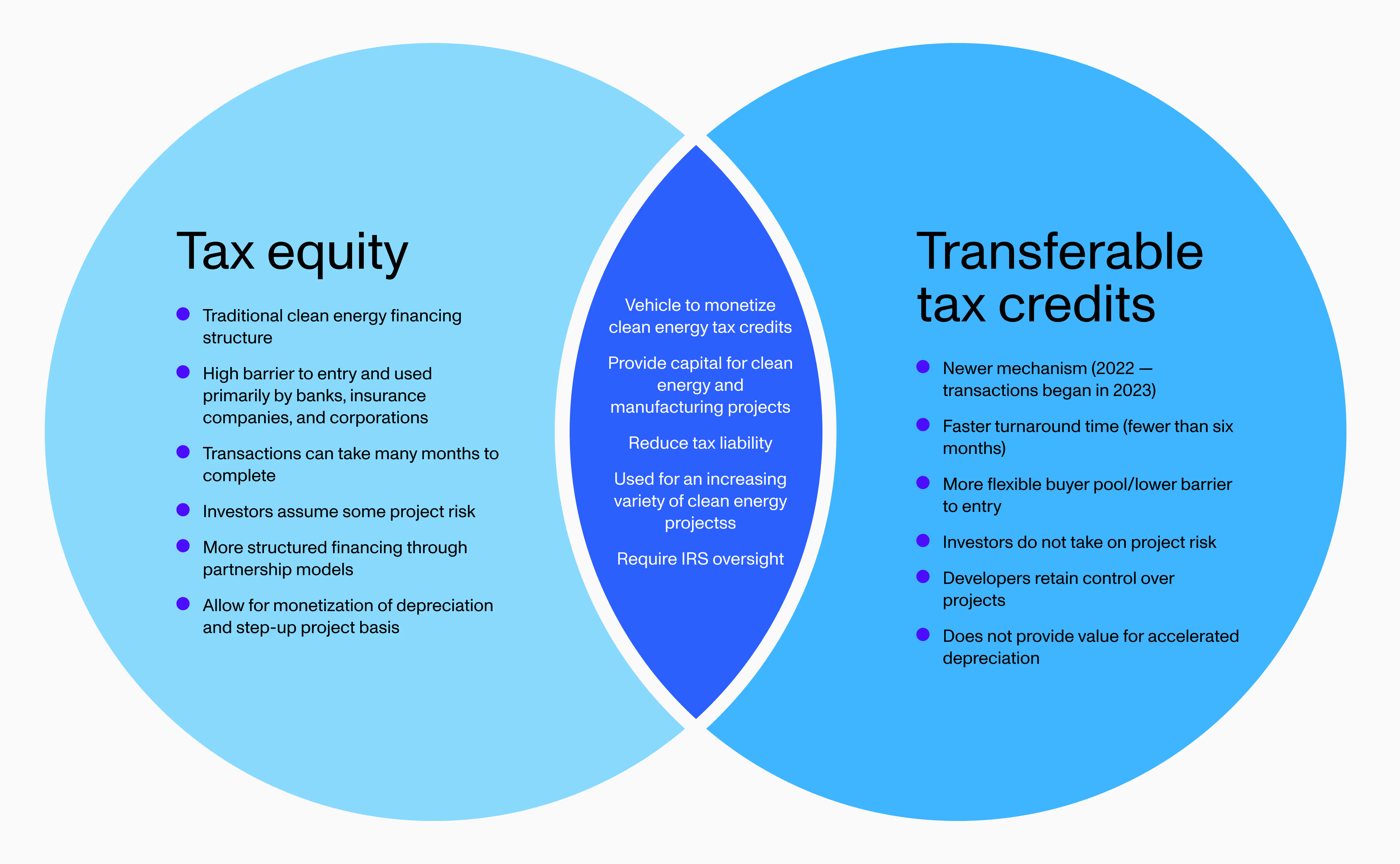

How are tax equity and transferable tax credit financing similar and different?

Tax equity:

Transferable tax credits:

What tax equity and transferable credit have in common:

Though well established, tax equity can be accessed only by a limited number of investors and developers due to its expense and complexity. Due to its simplicity relative to tax equity, transferability drives new investment into diverse energy. The two structures are complementary, providing developers flexibility to fund their projects.

For more information, check out the guide to transferable tax credits.

Because the availability of tax equity has been a constraint on project finance for clean energy, many tax equity partnerships are now structured to incorporate elements of transferability.

Hybrid tax equity financing gives investors and developers the flexibility to leverage the most attractive monetization features of both transferability and traditional tax equity partnerships. These structures, also known as T-flips, maintain the partnership structure of traditional tax equity deals. The T-flip name comes from the fact that the partnership also facilitates transferability — it is structured to permit the sale of transferable tax credits to a third party in a separate transaction. Depreciation benefits stay with the tax equity investor.

This financial structure is favored by investors who seek depreciation but can’t take full advantage of the tax credits. It also unlocks more capital via credits that are sold in the transfer market, expanding available funding from tax equity. This is a particularly important development for utility-scale projects with substantial tax equity needs.

Sales of clean energy credits from a tax equity partnership accounted for nearly 30% of the 2024 transferable tax credit market. This popularity is due to the benefits of the structure:

Developers and manufacturers need to understand their options and ask themselves a series of questions to identify the tax credit investment structure that best suits their project.

Steps to leverage tax equity for clean energy tax credits

Clean energy developers and manufacturers can take advantage of the ITC or the PTC. Deciding which to use means understanding both the project’s characteristics and the specific requirements to access the credits.

Capital-intensive projects such as utility-scale solar may benefit most from the upfront incentive provided by the ITC. Projects with high capacity factors that will produce significant amounts of electricity over a long period may do better utilizing the PTC. Eligibility to receive the ITC or PTC also depends on meeting construction-start and placed-in-service deadlines, which vary by technology.

Developers and manufacturers can increase the value of both the ITC and PTC by meeting requirements for bonus clean energy credits. These include credits for:

In the past, partnerships were the only way to use tax equity to finance clean energy. With the advent of transferability and the emergence of hybrid financing structures, developers and manufacturers must now assess which structure is most beneficial to their project. For smaller projects that need capital quickly, transferability is the obvious choice. But larger projects can still benefit from partnership with big banks and corporations.

The IRS has detailed requirements for receiving clean energy credits. Project developers and investors need to be aware of:

The best strategies to monetize tax credits depend on the investment structure and stakeholders.

Not all tax equity investors are the right fit for individual projects or portfolios of projects. Partners should have sufficient tax appetite and experience in both clean energy development and, ideally, the investment structure that works best for a project.

Tax equity structure options include:

The most efficient and effective tax equity partnerships develop over time as investors and developers gain confidence and familiarity with how each organization functions and the strength and expertise both provide. This shared experience helps in choosing a mutually beneficial deal structure and executing it effectively. Tax equity partnerships are complex, so it’s important to be realistic about the months necessary to complete transactions. As those transactions proceed, keep in mind the documentation necessary to comply with IRS regulations and respond to an audit.

Market activity in 2024 demonstrated the demand for hybrid structures that combine traditional tax equity partnerships with transferability. In a T-flip structure, allocating the clean energy credits between transferability and tax equity often depends on the tax equity investor’s tax appetite. If the investor doesn’t need to monetize all the credits to meet their tax liabilities, transferability can raise cash and enhance project economics. If a partnership transfers a meaningful amount of clean energy credits, the tax equity investor may require a larger share of depreciation or cash flow.

In a hybrid structure, developers must find the right investors and negotiate a deal that delivers value to both sides. Once the deal is finalized, it’s important to pay close attention to IRS compliance obligations, including the requirement to sell transferable credits in the year they are generated.

Transferability has greatly expanded the availability of clean energy credits to fund a wide array of technologies and project sizes. That accessibility is largely a function of the simplicity of transferability. Instead of being limited to large financial institutions and developers with the experience, project portfolio, and expertise to forge complex tax equity partnerships, transferability incentivizes the sale and purchase of clean energy credits by a much wider universe of parties.

Crux brings together the largest network of tax credit buyers and sellers in a single, tech-enabled platform. Our market-validated standards and purpose-built tools help developers and manufacturers transact with efficiency and transparency. Contact us to start using the Crux platform.